Earlier, we explored the hidden drivers of our minds behind why we think, judge, and decide the way we do. We then examined how we evolved to have such drivers. Based on all these, we can influence and be influenced by others to buy, donate, assent, and even vote, among other things.

Our world is complex and fast-paced. We face many decisions and situations every day, and we don’t have the time, energy, or capacity to think through each one.

So, we evolved to be guided by our intuitions instead of reasoning about everything we encounter. Our process works most of the time but it isn’t perfect. Sometimes, our automatic reactions aren’t the best response to a situation. And as our intuitions automatically respond to a situation, they are vulnerable to influence.

The key intuitive principles we all use, which are potent for influence, evolved with us. They helped us develop effective groups that outcompeted rivals. Such groups survived to form the societies we have today. As such, we have the principles encoded in our genes and are present from birth. We reinforce them by learning from the norms in our communities.

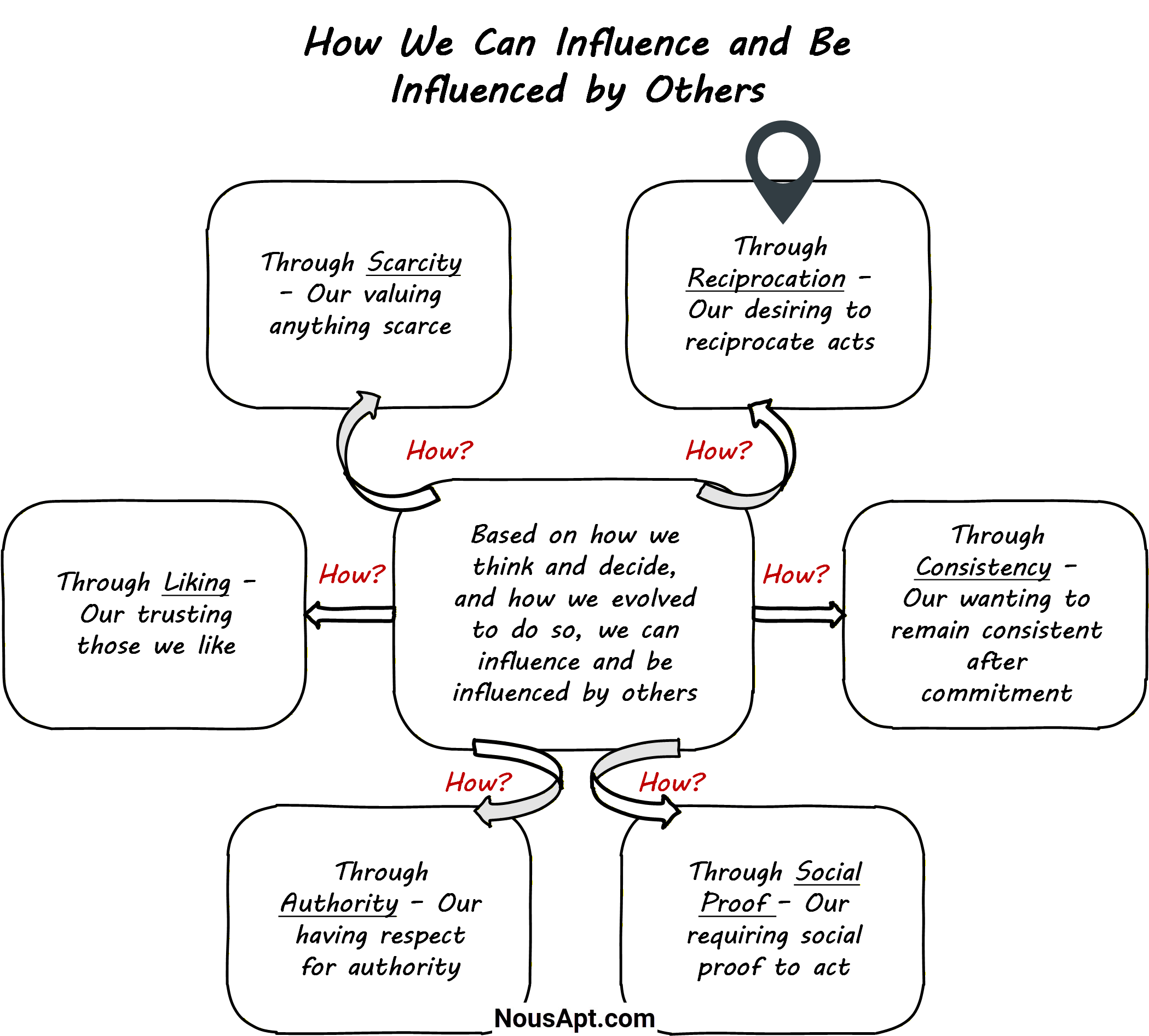

Robert Cialdini, in “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion,” outlined these principles of influence as:

- Reciprocation – Desiring to reciprocate acts

- Consistency – Wanting to remain consistent after commitment

- Social Proof – Requiring social proof to act

- Authority – Having respect for authority

- Liking – Trusting those we like

- Scarcity – Valuing anything scarce

In this post, we will explore reciprocation. But before we do, let’s further examine the link between our mental shortcuts and influence.

Subscribe for the Full Experience, It’s Free

View the complete post with deeper insights, practical applications, key takeaways, and more. Plus, you can download the post as a PDF document for printing or offline reference.

Subscribe once and gain access to other exclusive resources on the website and in your inbox.

More on Our Mental Shortcuts and Influence

As earlier explored, much of human action is automatic in dealing with a complex world. We often use shortcuts, our guides of sorts, to classify things according to a few key features. We then respond automatically without thinking when one or another of these trigger features is present.

For example, a common shortcut we use is that “expensive = good”. We commonly use it to guide our buying. And high prices become a trigger feature for quality, especially if we are quality-hungry buyers.

Yes, sometimes the behavior that unfolds may not be appropriate for the situation. This is because even the best shortcuts and trigger features do not always work as intended. But we accept the imperfection, since there is no other choice.

Without them, we wouldn’t make any progress as we think through everything while opportunities pass us by.

So, because our shortcuts are automatic and beyond our control, they make us vulnerable to anyone who knows how they work. It allows them to influence us. And they can do this without the appearance of influence.

Even those influenced tend to view their compliance as determined by natural forces, rather than by the designs of the person who benefits from their compliance.

Let’s illustrate how one can subtly influence people by design using the contrast principle.

The Contrast Principle

As Cialdini notes, this is a principle in human perception. It affects the way we see the difference between two things presented, one after another.

If the second item differs from the first, we tend to see it as more different than it is. So, if we first see a light object and then a darker object, we will estimate the second object to be darker. At least darker than if we had seen it without first seeing the light one.

Perhaps, before we delve into the key principles, it’s worthwhile noting that people often act in their self-interest. They want to get the most for their money and pay as little as possible. We all have the desire to maximize benefits and minimize costs. It’s an established factor of influence.

Having said that, let’s now explore each principle in more detail. As earlier stated, here we examine reciprocation. We will explore the consistency, social proof, authority, liking, and scarcity principles in subsequent posts.

Reciprocation – Desiring to Reciprocate Acts

One of the most potent of the weapons of influence around us is the rule of reciprocation.

The rule says that we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us.

As suggested in an earlier post, the rule of reciprocity has been with us as we evolved. It was crucial in our formation of tribes, cities, and today’s nation-states.

There had to be ways for us to divide labor and exchange goods and services. This makes it possible for experts to develop. It also creates interdependencies that bind selfish individuals together into cohesive and efficient groups.

Reciprocity was one of such ways. Think about it. If I could trust that you would reciprocate an act, I would cooperate with you for our mutual benefit. It became an obligation to reciprocate. The failure to do so had serious reputational consequences. And it makes it harder for the defaulter to get further cooperation within the group.

So, a strong feeling of future obligation made an enormous difference in how we evolved. This is because it meant that one person could give something to another and do so with confidence that it was not lost.

It lowered our reluctance to transactions that must begin with one person giving resources to another.

As a result, sophisticated and coordinated systems of aid, gift-giving, defense, and trade became possible. This brings immense benefits to the societies that have them.

It’s no wonder that societies train their members and make sure they follow and believe in it.

Each of us lives up to the rule, and each of us is aware of the social stigma associated with anyone who violates it. No one wants to be an ingrate.

So, because there is a general distaste across cultures for those who take without giving, we go to great lengths not to be one of them.

It’s to those lengths that we take, we will often be “taken” by those who stand to gain from our indebtedness.

The questions then are why reciprocation and how can one use it for influence?

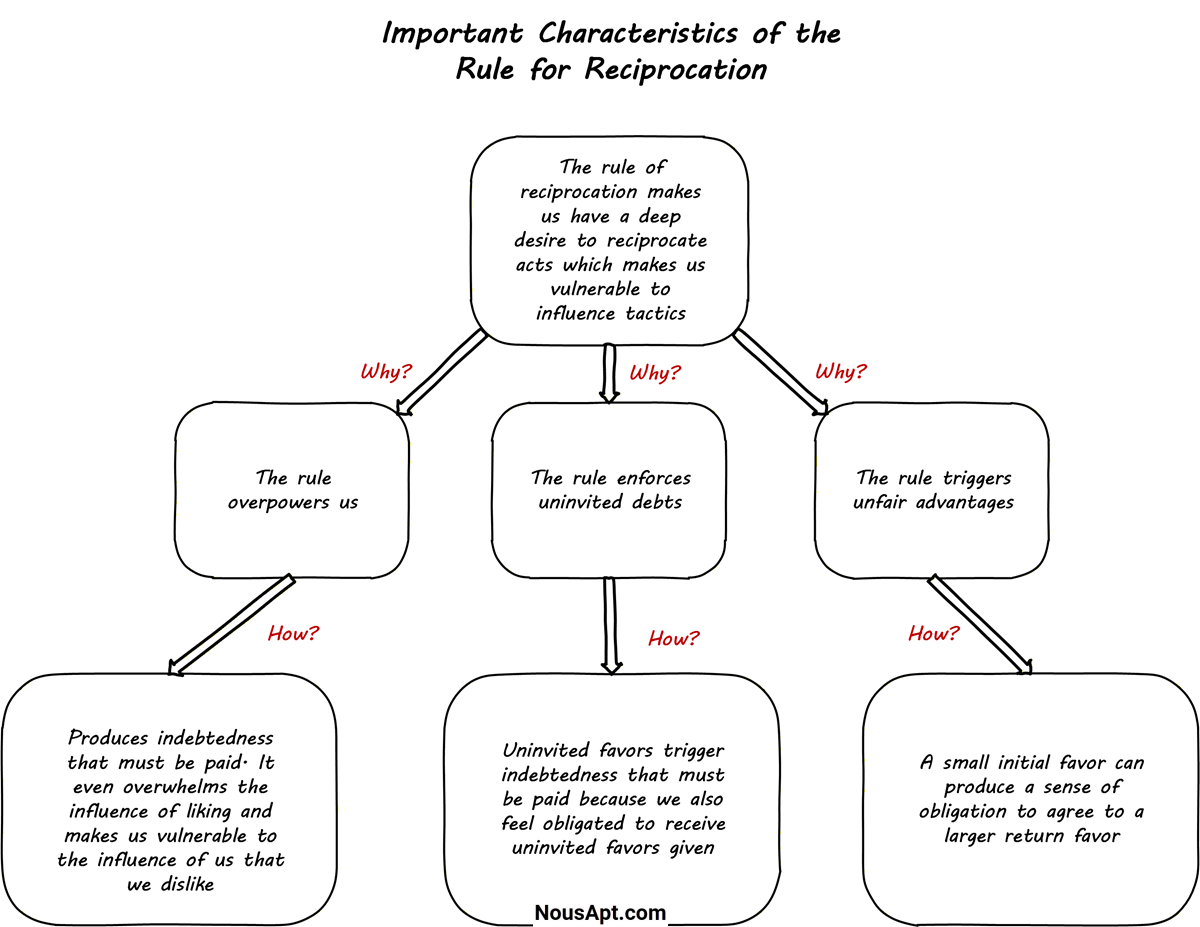

To answer these, Cialdini outlined the following important characteristics of the rule for reciprocation. It helps us understand why and how it can be profitably used. They include the rule:

- Overpowers

- Enforces uninvited debts

- Triggers unfair advantages

Overpowering

The rule for reciprocation is overpowering. It often produces a “yes” response to a request that, except for a feeling of indebtedness, would be refused.

Research findings, as reported by Cialdini, showed that the rule was so strong that it overwhelmed the influence of liking. Another influence principle that also affects the decision to comply.

Think of the implications. People we dislike can increase the chance that we will do what they wish by providing us with a small favor before their request.

Enforcing Uninvited Debts

The reciprocity rule, besides its power, enforces an uninvited debt. Another person can trigger a feeling of indebtedness by doing us an uninvited favor.

Recall that the rule only states that we should provide to others the kind of actions they have provided us. It does not need us to have asked for what we have received to feel obligated to repay.

This is not to say that we will not feel a stronger sense of obligation to return a favor we have requested. Only that such a request is not necessary to produce indebtedness.

If we reflect for a moment on the social purpose of the reciprocity rule, we can see why this is the case.

The rule promotes the development of reciprocal relationships between individuals. Allowing one person to start such a relationship without fear of loss. If the rule is to serve its purpose, then an uninvited first favor must have the ability to create an obligation.

Remember that the reciprocity rule gives great advantage to cultures that foster it. Hence, there is intense pressure to ensure that the rule serves its purpose.

The anthropologist Marcel Mauss, author of “The Gift”, in describing the social pressures surrounding the gift-giving process in human culture, stated that:

“There is an obligation to give, an obligation to receive, and an obligation to repay.”

Although the obligation to repay is the essence of the reciprocity rule, it is the obligation to receive that makes the rule so easy to exploit. The obligation to receive reduces our ability to choose whom we wish to owe. It puts that power in the hands of others.

Triggering Unfair Advantages

The reciprocity rule promotes equal exchanges between partners. But a partner can use it to achieve unequal results.

The rule requires that one type of action be reciprocated with a similar type of action. However, the interpretation of the “similar type of action” is quite flexible.

A small initial favor can produce a sense of obligation to agree to a larger return favor.

As we have already seen, the rule allows one partner to choose the nature of the first favor and the nature of the debt-cancelling favor. So, we could easily be manipulated into an unfair exchange by those who wish to exploit the rule.

For example, a marketer offers a free sample in exchange for a large business account. That’s an unequal exchange.

Why should it be that small first favors often stimulate larger return favors?

One important reason concerns the unpleasant character of the feeling of indebtedness. Most of us find it disagreeable to be in a state of obligation. It weighs heavily on us and demands that we remove it.

For this reason alone, we may be willing to agree to perform a larger favor than we received to relieve ourselves of the psychological burden of debt.

But there is another reason as well. Remember that a person who violates the reciprocity rule is actively disliked.

Because of this, we will sometimes agree to an unequal exchange.

So far, we have looked at the reciprocity rule through the direct route of offering a partner a favor and asking for one in return.

There is a second, more subtle way to use the reciprocity rule to get someone to comply with a request. In some ways, it’s more effective than the direct approach. We will explore it next.

Concessions Also Need Reciprocation

The reciprocity rule states that a person who acts in a certain way towards us gets a similar response.

We have already seen that one consequence of the rule is an obligation to repay favors we receive. Another consequence of the rule, yet, is an obligation to concede to someone who has conceded to us.

Why should we feel a strain to reciprocate a concession?

The answer rests once again in the benefit of such a tendency to a society. Of course, it’s in the interests of any human group to work together toward achieving shared goals.

But in many interactions, the parties begin with demands that are unacceptable to one another. So, the group must arrange to have those initial demands set aside for the sake of cooperation. This is accomplished through procedures that promote compromise. Mutual concession is one crucial such procedure.

So, because of the rule of reciprocation, it is possible to use an initial concession as part of a highly effective influence technique.

The technique is a simple one that we can refer to as the rejection-then-retreat technique. This is as suggested by Cialdini.

The Rejection-Then-Retreat Technique in Action

Suppose you want me to agree to a specific request. One way to increase your chances would be first to make a larger request of me, one that I will most likely turn down. Then, after I have refused, you would make the smaller request that has always interested you.

If you structured your serial request skillfully, I should view it as a concession to me. And feel inclined to respond with a concession of my own. The only one I would have immediately opened to me is compliance with your second request.

Labor negotiations, for instance, often use the tactic. They start with extreme demands that they do not expect to win. From which they retreat in a series of seeming concessions. All designed to draw out the real concessions from the opposing side.

It appears, then, that the larger the initial request, the more effective the procedure. There is more room available for illusory concessions.

But this is true only up to a point. Cialdini reported that research conducted at Bar-Ilan University in Israel on the technique shows that if the initial demand is unreasonable, the tactic backfires.

In such cases, the party that makes the initial extreme request is not seen to be bargaining in good faith. Any retreat from the unrealistic position is not viewed as a genuine concession. And it’s not reciprocated.

In general, to see the power of reciprocation at scale, look to social media platforms. When someone engages with your content, you feel subtle pressure to reciprocate. These platforms have essentially automated the reciprocity rule. They turn social obligations into engagement metrics and profitability.

How To Say No to Reciprocation

How do we go about neutralizing the effect of a social rule like that for reciprocation?

Cialdini suggested that we accept the desirable first offers of others. But to accept those offers only for what they fundamentally are, not for what they are represented to be.

If a person offers us a nice favor, we should accept. We do so recognizing that we have obligated ourselves to return the favor sometime in the future.

This sort of arrangement does not exploit the rule of reciprocation. Quite the contrary. It is to participate fairly in the” honored network of obligation.” This has served us so well, both individually and societally, from the dawn of humanity.

But if the initial favor turns out to be a device, a trick designed to stimulate our compliance with a larger return favor. Then, that is a different story.

Here, our partner is not a benefactor but a profiteer. And it’s here that we should respond to his action on precisely those terms.

He no longer has the reciprocation rule as an ally. The rule states that favors are to be reciprocated with favors. It does not require that tricks be reciprocated with favors.

In such situations, we can accept or reject a gesture without feeling the need to reciprocate. Why? Because it wasn’t a gesture made in good faith.

It’s worth mentioning that people are becoming more aware of calculated tactics. They’re better able to distinguish between genuine favors and artificial devices.

Perhaps this explains why free samples or free trials nowadays may not be as effective as they once were due to abuse.

Conclusion

Reciprocation is a powerful principle that has served humanity well across time and cultures. It facilitates the exchange of ideas, goods, and services. It enables trust, cooperation, and the building of complex societies.

But, like any powerful tool, it can help create genuine value or exploit others.

The key is to:

- Give value when you want to build real relationships

- Receive genuine favors with genuine intent to reciprocate

- Recognize devices designed to create false obligations

- Respond appropriately by accepting favors as favors and tricks as tricks

Indeed, reciprocation is one of the most potent weapons of influence. To make the most of it, build a reputation for delivering genuine value. It will always outperform short-term reciprocity manipulation. Focus on giving value to others and reciprocation will flow naturally.

In the next post, we will explore consistency, another potent weapon of influence.

Understanding these principles of influence helps you get better at persuading and resisting exploitation.

If you found this post helpful, imagine how much more value you will get from it as a subscriber. Plus, you can download the post as a PDF document for printing or offline reference.

Lastly, you will love our newsletters where we share exclusive resources with subscribers. Subscription is free.

To share your views on this post, take the discussion to your favorite network. Use the share buttons below.

I am the managing director of Proedice Limited where we help organizations and individuals get remarkable results from entrepreneurship, innovation, and marketing. I am constantly learning and always looking to make a positive impact.