This post continues our series exploring the most potent weapons for influence. To make the most of the series, start with the foundational post and follow through.

In a few words, we face many decisions and situations every day and don’t have the time, energy, or capacity to think through each one. So, we evolved to have our intuitions guide us instead of reasoning everything. Because our intuitions respond automatically to situations, they are vulnerable to influence.

The key intuitive principles we all use, which are potent for influence, evolved with us. They helped us develop effective groups that outcompeted rivals. Such groups survived to form the societies we have today. As such, we have the principles encoded in our genes and are present from birth. We reinforce them by learning from the norms in our communities.

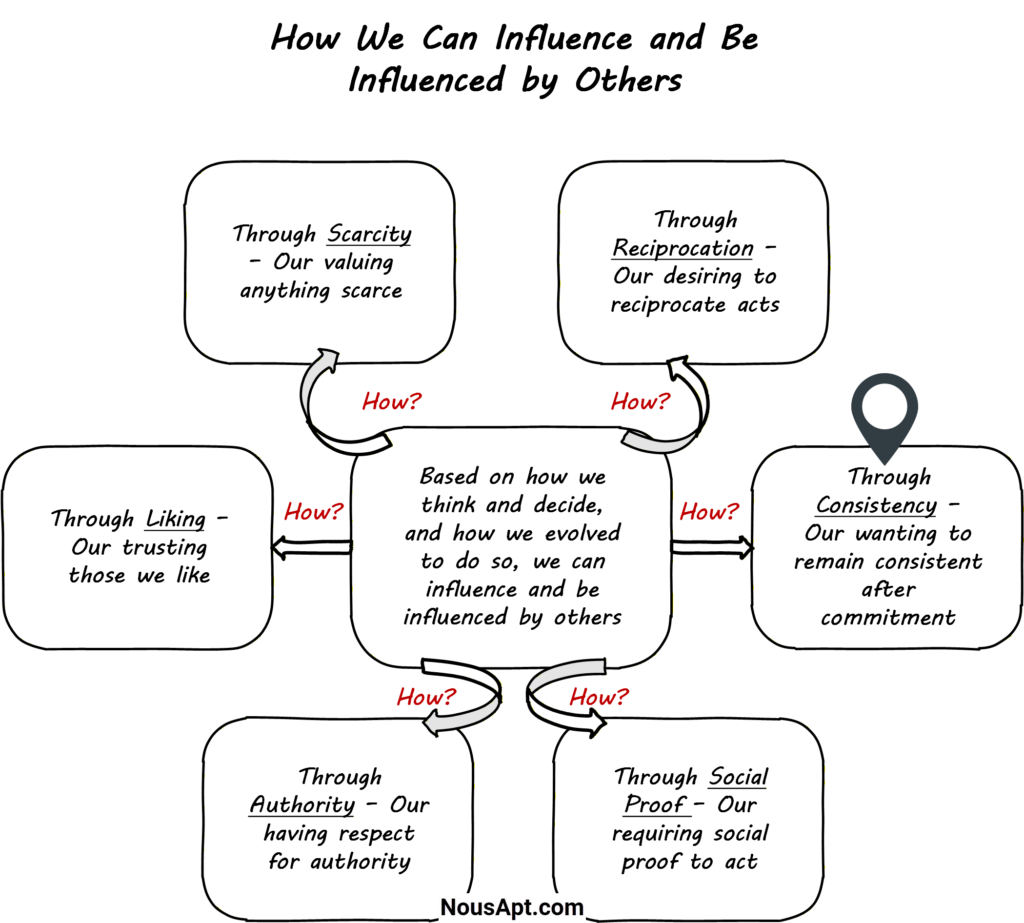

In “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion,” Robert Cialdini outlined these principles of influence as:

- Reciprocation – Desiring to reciprocate acts

- Consistency – Wanting to remain consistent after commitment

- Social Proof – Requiring social proof to act

- Authority – Having respect for authority

- Liking – Trusting those we like

- Scarcity – Valuing anything scarce

In this post, we will explore consistency. But before we do, you really should read the foundational post if you haven’t. It further examines the link between our mental shortcuts and influence.

Subscribe for the Full Experience, It’s Free

View the complete post with deeper insights, practical applications, key takeaways, and more. Plus, you can download the post as a PDF document for printing or offline reference.

Subscribe once and gain access to other exclusive resources on the website and in your inbox.

Consistency – Wanting to Remain Consistent After Commitment

Another principle of influence that quietly directs our actions is our desire to look consistent with our past actions.

Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we are pressured to behave consistently with that commitment.

It stems from our decision-making process, specifically the social intuitionist model. Our intuition makes a quick decision. And our reasoning comes after to justify such a decision. Hence, the pressure to respond in ways that justify our earlier decision.

Cialdini notes a study that uncovered something fascinating about bettors at the racetrack. Just after placing a bet, bettors are much more confident of their horse’s chances of winning. They were much more so than immediately before laying down that bet.

The bettors’ actions make sense when you apply the consistency principle, don’t they?

Thirty seconds before putting down their money, they were uncertain. Thirty seconds after the deed, they were much more optimistic and self-assured. The act of making a final decision, in this case, of buying a ticket, had been the critical factor.

Once their intuition leads them to back the horse, their reasoning justifies it. The need for consistency aligns their feelings and beliefs with their existing actions.

They convinced themselves that they had made the right choice and, no doubt, felt better about it all.

Consistency is such a powerful motive. And in most circumstances, it’s valued and adaptive. It’s essential to understand why. Wouldn’t you agree?

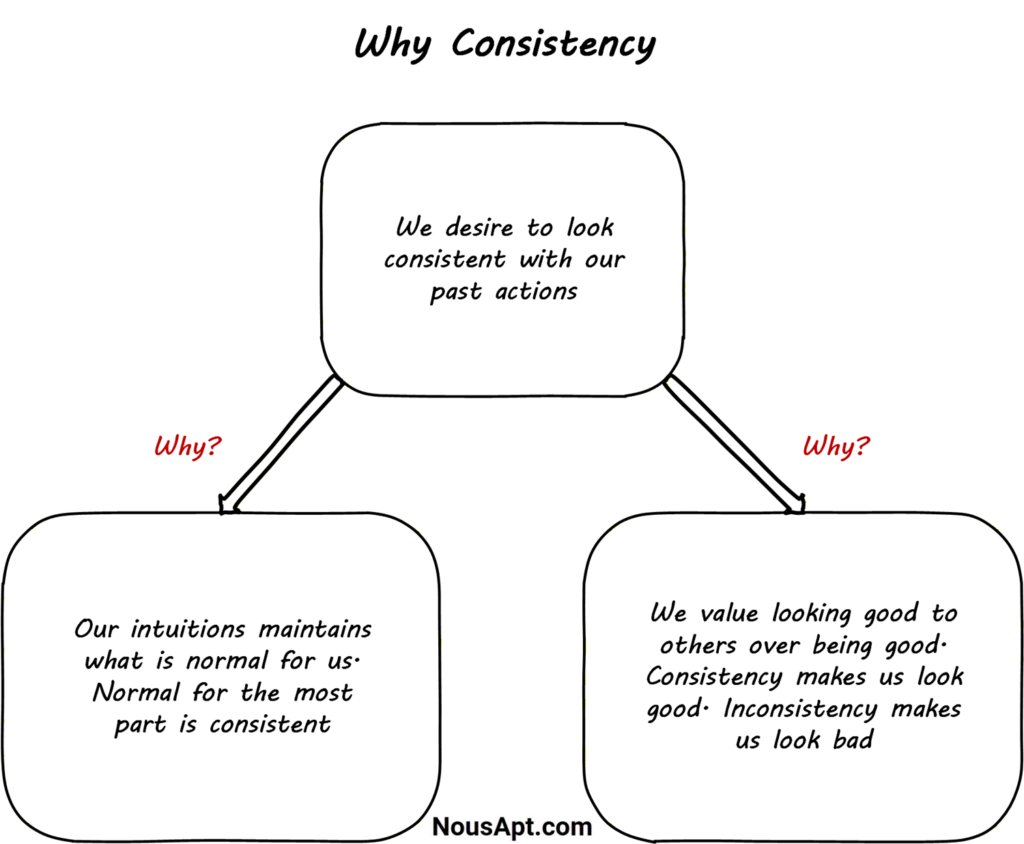

Why Consistency

Our intuition’s main function is to maintain and update a model of our world which presents what is normal to us. So consistency becomes invaluable. Normal for the most part is consistent.

Additionally, we often focus on looking good to others over actually being good.

Inconsistency is often regarded as an undesirable personality trait. It doesn’t help us look good.

The person whose beliefs, words, and deeds don’t match seems indecisive, confused, two-faced, or even mentally ill. In other words, we see the person as untrustworthy, which looks bad.

But a high degree of consistency is associated with personal and intellectual strength. It is at the heart of logic, rationality, stability, and honesty. In other words, we see a consistent person as trustworthy, which looks very good.

So, good personal consistency is highly valued in our cultures, as it should be. It provides us with a reasonable and gainful orientation to the world. Most of the time, we will be better off if our approach to things is consistent. Without it, our lives would be difficult, erratic, and disjointed.

Because it is in our best interest to be consistent, we easily fall into the habit of being automatically so. Sad to say, even in situations where it’s not the sensible way to be.

You see common examples on social media. People post their political opinions or lifestyle choices publicly. Then they stick to that image due to the enormous pressure to remain consistent. Most times, even when faced with superior arguments, they do not change their position.

So a fitness influencer who posts about healthy living maintains that persona even when struggling to do so in private.

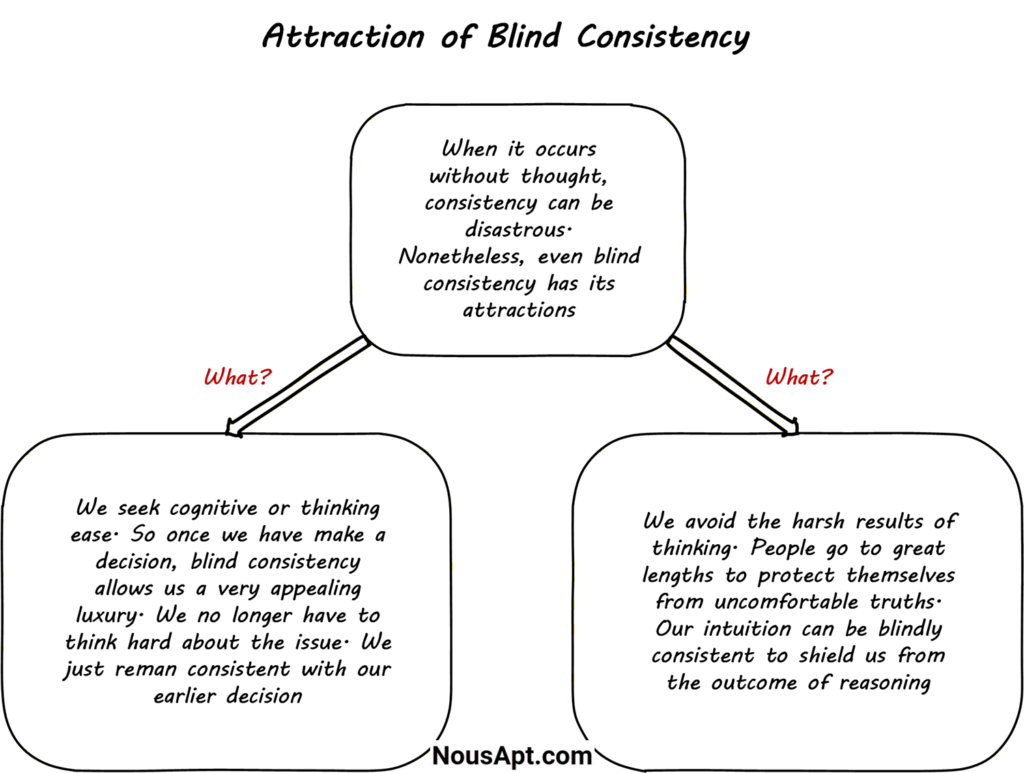

When it occurs without thought, consistency can be disastrous. Nonetheless, even blind consistency has its attractions.

Attraction of Blind Consistency

First, consistency offers us a shortcut through the maze of modern life. Quite like most other forms of automatic or intuitive responding,

We always seek cognitive or thinking ease. So once we have made up our minds about an issue, stubborn consistency allows us a very appealing luxury. We no longer have to think hard about the issue.

Instead, when confronted with the issue, all we have to do is turn on our consistency tape. Then we know just what to believe, say, or do. That is whatever is consistent with our earlier decision.

So, it’s not hard to understand why automatic consistency is a difficult reaction to control. It offers us a way to evade the rigors of continuing thought.

And as Sir Joshua Reynolds said,

“There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.”

There is a second, more unreasonable attraction of blind consistency as well. Sometimes it is not the effort of hard, cognitive work that makes us avoid thinking. It is the harsh results of that thinking.

At times, it is the annoying, clear, and unwelcome set of answers provided by straight thinking that makes us not want to think.

There are certain disturbing things we would rather not realize. Because it’s automatic, blind consistency can supply a safe hiding place from such. Our intuition can be blindly consistent to shield us from the outcome of reasoning.

Indeed, people will go to great lengths to protect themselves from uncomfortable truths.

A Telling Illustration

Cialdini provided a compelling illustration using an introductory lecture they once attended. He and his colleague attended a lecture by the Transcendental Meditation (TM) program. There, he saw how people hide inside the walls of consistency to protect themselves from the troublesome consequences of their thoughts.

The lecture was designed to recruit new members into the program. The program claimed it could teach a unique brand of meditation that would allow attendees to achieve a range of desirable outcomes. Such outcomes range from simple inner peace to more spectacular abilities. This includes such abilities as flying and passing through walls at the program’s advanced stages. As you might expect, the advanced stages were much more expensive.

When it was time for questions after the lecture, Cialdini’s colleague raised his hand. He gently but surely demolished the presentation they had just heard. His colleague was a professor of statistics and symbolic logic.

The effect of his argument on the program leaders was devastating. But more interesting was the effect on the rest of the audience. The audience rushed to submit their payments for admission to the TM program.

Although puzzled, Cialdini summed up the audience’s response to a failure to understand the logic of his colleague’s arguments. But, as it turned out, the reverse was the case.

When asked, three of the attendees he spoke with said they understood his colleague’s comment quite well. It was precisely the strength of his argument that drove them to sign up for the program on the spot.

One of the three puts it best:

“Well, I wasn’t going to put down any money tonight because I’m quite broke right now. I was going to wait until the next meeting. But when your buddy started talking, I knew I’d better give them my money now, or I’d go home and start thinking about what he said and never sign up.”

It’s About Hope – Even False Hope

Members of the audience for the lecture were people with really difficult problems. And they were somewhat desperately searching for a way to solve those problems. They were seekers who had found a potential solution in TM. Driven by their needs, they very much wanted to believe that TM was their answer.

Now, in the form of Cialdini’s colleague, the voice of reason intrudes, showing the theory underlying their newfound solution to be unsound.

They had to do something before logic takes its toll and leaves them without hope again.

It’s like what we see with some religious, political, and business followers nowadays. Some people desperately want to hold on to the utopian hope they found in a movement. No argument to the contrary shifts their position. Blind consistency shields them from the outcome of thinking. It puts them back in their messy reality. It also makes them perfect candidates for exploiters.

Taking Advantage of Blind Consistency

Automatic or blind consistency discourages thought. So, it should not be surprising that such consistency can be exploited for influence.

For exploiters, an unthinking, mechanical reaction to their requests serves their interest. The tendency toward automatic consistency is a gold mine to them.

Some large toy manufacturers use consistency to their advantage to address a problem caused by seasonal sales.

Before Christmas, they advertise special toys. Kids, seeing such adverts, extract Christmas promises for the toys from their parents.

The companies then undersupply stores with the toys they have gotten parents to promise their kids. Most parents find those toys sold out and are forced to substitute for other toys of equal value. The toy manufacturers ensure the stores are supplied with plenty of these substitutes.

Then, after Christmas, the companies start rerunning the ads for the earlier special toys. This makes kids want those toys more and run to their parents to remind them of their promise. The parents, needing to remain consistent, head to the store to fulfill their promise.

Commitment Is the Key

By now, it should be obvious how powerful consistency is in directing human action. The question then is, how can we engage consistency for influence?

Social psychologists suggest the answer is commitment as you might have guessed.

If I can get you to make a commitment, I will have set the stage for your automatic and ill-considered consistency with that earlier commitment.

So to influence you, I should get you to take a stand or to go on record. There is then a natural tendency for you to behave in ways that are stubbornly consistent with the stand.

Here is an example to drive this point home.

Suppose you wanted to increase the number of volunteers for your favorite charity. Cialdini suggested that you study the approach taken by social psychologist Steven J. Sherman.

He called a sample of residents in a US area as part of a survey he was taking. He then asked them to predict what they would say if asked to spend time collecting money for charity. Of course, not wanting to seem uncharitable, many said they would volunteer.

The commitment resulted in a 700 percent increase in volunteers when someone from the American Cancer Society called to ask for volunteers a few days later.

The Foot-In-The-Door Technique

The tactic of starting with a small request to gain eventual compliance with a related larger request has a name. The foot-in-the-door technique, as suggested by Cialdini.

Because of the technique, we should be careful about agreeing to trivial requests. Such an agreement can increase our compliance with similar larger requests. It can also make us more willing to perform large favors that are not connected to the little ones we did earlier. It’s this second, general kind of influence hidden in small commitments that should scare us.

Once we form a new self-image (after a commitment), we want to be consistent with it. And all sorts of advantages become available to someone who wants to exploit that new image.

Experts in the foot-in-the-door technique know one thing. You can use small commitments to manipulate people’s self-image. You can turn prospects into “customers,” and citizens into “public servants”.

And once you have got a man’s self-image where you want it, he should comply with your requests that are consistent with this view of himself.

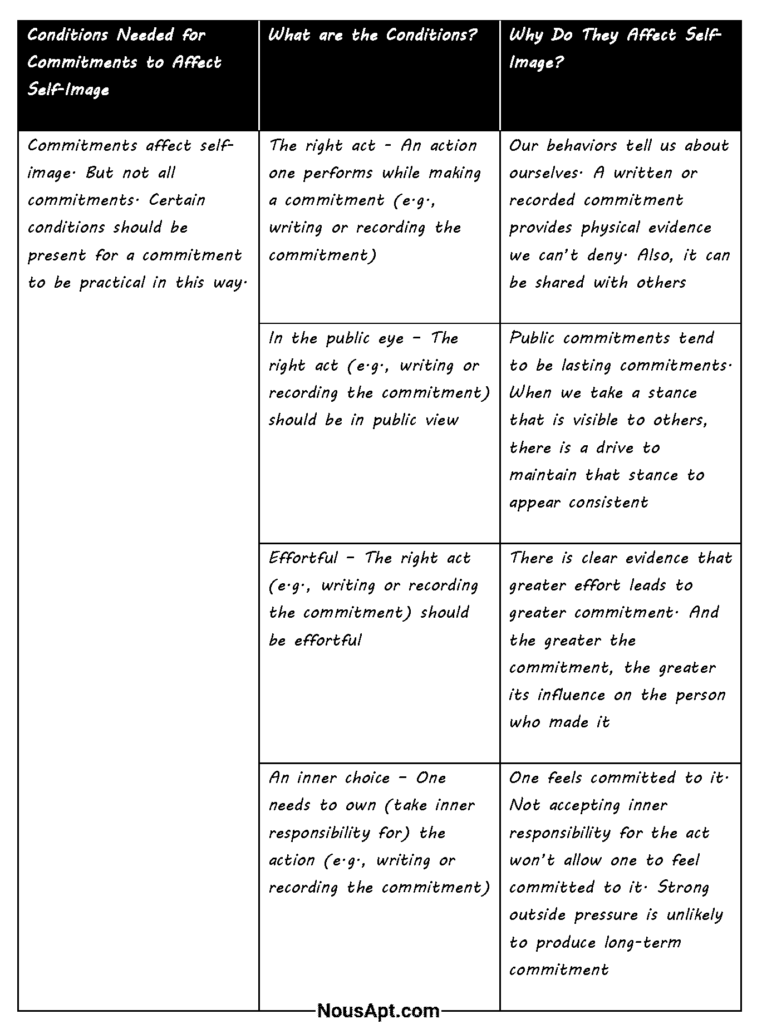

But not all commitments affect self-image. Certain conditions should be present for a commitment to be practical in this way.

Conditions Needed for Commitments to Affect Self-Image

The conditions include that the commitment needs to be:

- The right act

- In the public eye

- Effortful

- An inner choice

The Right Act

Our best evidence of what people truly feel and believe comes from their actions. And less from their words.

Observers trying to decide what a man is like look closely at his actions. We also determine what we are like by our actions.

Our behavior tells us about ourselves. It is a primary source of information about our beliefs, values, and attitudes.

So if we understand this, we can arrange experiences that get people we want to influence to act in desired ways. Before long, these actions cause them to change their views of themselves to align with what they had done (their acts).

Writing is one sort of confirming action that we can urge all the time on the people we want to influence. Another confirming action is a recording, either an audio or a video recording. It’s not enough for someone to listen or even to agree verbally with what we say. They should always write or record it down as well. It’s so important that if someone is not willing to write or record a desired response, we should persuade them to do one of the following:

- Copy it for writing

- Read it out for recording

- Copy it in their handwriting and read it out in a recording

As a commitment device, a written or recorded declaration has some great advantages.

First, it provides physical evidence that the act occurred. Once a man writes or records something down, it is very difficult to deny that he has done so.

The opportunities to forget or to deny to himself what he had done are not available. This is not the same for purely verbal statements.

No, it’s there in his handwriting, or a recording of his voice, a documented act. It drives him to make his beliefs and self-image consistent with his past actions.

A second advantage of a written or recorded statement is that it can be shared with others. It can persuade others to change their attitudes in the direction of the statement.

But even more important for getting the author to commit and stay consistent is that it can convince others that the author believes what he wrote or recorded. This puts pressure on the author to remain consistent to look good. Remember that looking consistent is good.

People Believe Statements

People have a natural tendency to think that a statement reflects the true belief of the person who made it. What is surprising is that they continue to think so even when they know the person did not freely choose to make the statement.

Some evidence for this comes from a study by psychologists Edward Jones and James Harris. They showed people an essay that was favorable to Fidel Castro and asked them to guess the true feelings of its author.

Jones and Harris told some of these people that the author had chosen to write a pro-Castro essay. And they told the other people that the author had been required to write in favor of Castro.

The strange thing was that even those people who knew that the author had been assigned to do a pro-Castro essay guessed that he liked Castro.

It seems that a statement of belief produces an automatic response in those who view it. Unless there is strong evidence to the contrary, observers automatically assume that someone who makes such a statement means it.

Imagine a judge or jury presented with a written or recorded confession. And imagine a defense attorney arguing that it was forced. What do you think the judge or jurors will do? Ignore the written or recorded confessions? Unless there is supporting evidence, they may assume that the confession is valid.

What those around us think is true of us is very important in determining what we ourselves think is true.

So once we make an active commitment, consistency pressure squeezes our self-image from both sides.

From the inside, there is a pressure to align self-image with actions. From the outside, there is a sneakier pressure: a tendency to adjust this image according to how others perceive us.

And because others see us as believing what we have written or recorded (even when we’ve had little choice in the matter), we will experience a pull to align our self-image with the statement.

In the Public Eye

One reason that written or recorded testaments are effective in bringing about genuine personal change is that they can so easily be made public.

Public commitments tend to be lasting commitments.

When one takes a stance that is visible to others, there is a drive to maintain that stance to appear consistent.

For appearances’ sake, the more public a stance, the more reluctant we will be to change it. Even in situations where accuracy should be more important than consistency, we stubbornly refuse to change our public stance. It ties back to our need to look good rather than be good.

Organizations dedicated to helping people overcome bad habits, such as losing weight, understand this. Often, a person’s private decision to lose weight will be too weak to withstand temptations.

So, they ensure that the decision is a public commitment. They ask their clients to write down an immediate weight-loss goal and show it to as many friends, relatives, and neighbors as possible. Clinic operators report that this technique often works where all else has failed.

Effortful

Another reason that written or recorded commitments are so effective is that they take more effort than verbal ones. There is clear evidence that greater effort leads to greater commitment. And the greater the commitment, the greater its influence on the attitudes of the person who made it.

Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills did a study in 1959 to test their observation that:

People who go through a great deal of trouble or pain to attain something tend to value it. And they value it much more than people who attain the same thing with minimal effort.

They found that college women who endured a very embarrassing initiation ceremony to join a sex discussion group convinced themselves that their new group and its discussions were extremely valuable.

This is even as Aronson and Mills had earlier coached the other group members to be as “worthless and uninteresting” as possible.

Those who went through a much milder initiation ceremony, or no initiation at all, were clear about how “worthless” the new group they joined is.

More research showed the same results when coeds endured pain instead of embarrassment to get into a group. The more electric shocks a woman received as part of an initiation ceremony, the more she persuaded herself that the new group and its activities were valuable.

Now the harassments, exertions, and even the beatings of initiation rituals begin to make sense.

They are acts of group survival. They make future society members find the group more attractive and worthwhile. And as long as people like and believe in what they struggled to get, these groups will continue to arrange effortful and troublesome initiation rites.

This is because the loyalty and dedication of those who emerge will greatly increase the chances of group cohesiveness and survival.

Military groups and organizations make the most of these processes. The pains of initiation into the armed services are well known.

The extensive training makes successful candidates much more committed to the military.

An Inner Choice

It appears that commitments are most effective in changing a person’s self-image and, hence, their behavior when they are active, public, and effortful. But there is another condition that is more important than the other three (3) combined.

The need to own the action. It’s not enough to get commitments out of people. There is a need to make those people take inner responsibility for their actions. This is as determined by social scientists.

We accept inner responsibility for a behavior when we think we choose to perform it without strong outside pressures. A large reward is one such external pressure. It may get us to perform a certain action, but it won’t get us to accept inner responsibility for the act. So, we won’t feel committed to it.

The same is true of a strong threat. It may motivate immediate compliance, but it is unlikely to produce long-term commitment.

Inner Change Keeps Giving

As already explored, those seeking influence love commitments that produce inner change.

First, that change is not just specific to the situation where it first occurred. It covers a whole range of related situations, too.

Second, the effects of the change are lasting. A man influenced to shift his self-image acts in line with that new self-image, at least for as long as it holds. So, a man with a new self-image of a public-spirited citizen is likely to be public-spirited in a variety of other circumstances as desired.

There is yet another attraction in commitments that lead to inner change. They grow their own legs. There is no need to undertake a costly and continuing effort to reinforce the change. The pressure of consistency will take care of all that.

Back to our man with the new public-spirited citizen self-image. After he comes to view himself as such, he will automatically begin to see things differently. He will:

- convince himself that it is the correct way to be.

- begin to pay attention to facts he hadn’t noticed before about the value of community service.

- make himself available to hear arguments favoring civic action he hadn’t heard before. And he will find such arguments more persuasive than before.

In general, he will convince himself that he is right in his choice to be a public-spirited person. His intuition registers his new norm (a public-spirited fellow) and responds as needed. And his reasoning follows to justify his actions to look consistent.

The process of his reasoning justifying the commitment with new reasons is important. Even if the original reason doesn’t hold, the new reasons might hold the self-image in place. So he might continue his civic-minded behavior based only on his new reasons.

The advantage of this for an exploitative party is tremendous.

An exploitative party can offer us an inducement to commit. And after we commit, the party can remove that inducement. They know that our commitments might still stand because we create new inducements.

Typically, we get a great offer that makes us want to buy. Then, sometime after we have committed but before we close the deal, what makes it great is deftly removed.

Some Businesses Get It

Automobile dealers seem to understand that a personal commitment builds its own support system by creating new justifications. Often, these justifications provide many legs for the decisions to stand on, so that even when the dealer pulls away the original one, there is no collapse.

The customer excuses the loss. He consoles himself, even becomes happy, by the other good reasons favoring the choice. It never occurs to him that those other reasons might never have existed if the taken reason hadn’t persuaded him in the first place.

How To Say No to Consistency

Indeed, consistency is vital. But there are times we shouldn’t be automatically so. It leaves room for exploiters to take advantage.

Cialdini suggested two kinds of signals to tip us off about those times.

The first kind of signal is easy to recognize. Our intuition warns us when a party traps us into complying with a request we know we don’t want to perform, but may do so to be consistent with the earlier commitment we were tricked into.

When that happens, you should tell the requester. Point out why it is foolish for you to comply with the request. While consistency is essential, foolish ones aren’t.

Whatever the requester’s reaction, be happy. You have saved yourself from exploitation.

High-pressure sales situations are precisely the right time to use this.

Listen to Your Heart of Hearts

Sometimes, our intuition may not catch on and warn us when we are being taken. In such situations, we have to look deeper for a clue.

We look to our “heart of hearts,” as people often say. It is the one place where:

- We are yet to form our intuition and reasoning about a matter.

- We cannot fool ourselves.

- None of our justifications, none of our rationalizations penetrate.

To get signals from our heart of hearts, we must answer this question:

- “Knowing what I now know, if I could go back in time, would I make the same choice?”

Let’s go back to the automobile dealers’ use of commitment and consistency, for example. Suppose a dealer uses an attractive offer to get you to commit. Then he later withdraws the offer, knowing that you have new justifications for your commitment. And you will most likely still close the sale.

In that situation, before closing the sale, you ask yourself:

- “Knowing what I now know (that the attractive first offer is not real), if I could go back in time, would I make the same choice (committing to closing the sale)?”

The answer you are looking for is a pure, basic feeling. Cialdini suggested that evidence indicates that we experience our feelings towards something a split second before we mentally process it.

So, if we are attentive, we should register the pure basic feeling just before our mental process engages.

The advice then is to look for and trust the first flash of feeling we experience in response.

This feeling would likely be a signal from our heart of hearts. It slips through undistorted just before the means we kid ourselves flood in.

Conclusion

The consistency principle helps us survive and thrive in our complex world. It helps build trust through predictable behavior. Yet it makes us vulnerable to exploitation.

The key is to be more conscious rather than blindly consistent all the time:

- Use consistency ethically to help you and others achieve each other’s goals

- Honor commitments that still serve your values and goals

- Change course when circumstances change significantly

- Build in regular review periods for all major commitments

- Recognize manipulation tactics and refuse to be trapped by trivial commitments

Remember that wisdom sometimes requires inconsistency with our past selves. The person who never changes their mind never learns anything new.

Your reputation is better served by thoughtful flexibility than rigid consistency. People respect those who can say:

“I’ve learned something new, and I’m adjusting my position accordingly.”

On the whole, you will agree that consistency is a very potent weapon of influence. Wouldn’t you?

In the next post, we will explore social proof, another potent weapon of influence.

Understanding these principles of influence helps you get better at persuading and resisting exploitation.

If you found this post helpful, imagine how much more value you will get from it as a subscriber. Plus, you can download the post as a PDF document for printing or offline reference.

Lastly, you will love our newsletters where we share exclusive resources with subscribers. Subscription is free.

To share your views on this post, take the discussion to your favorite network. Use the share buttons below.

I am the managing director of Proedice Limited where we help organizations and individuals get remarkable results from entrepreneurship, innovation, and marketing. I am constantly learning and always looking to make a positive impact.